Valentine’s Day is a minor holiday in the US (the banks and the government are open for business) that celebrates romance and affection. But in Chicago in 1929, in a garage on North Clark Street, a different kind of Valentine’s Day unfolded: a brutal massacre orchestrated by none other than Al Capone.

Al Capone’s south side gang was in a turf war with the north side operation of George “Bugs” Moran. Back then, illegal drugs consisted of beer, wine, and whiskey (along with today’s pharmacopeia), and whoever supplied Chicago’s speakeasies made millions.

Prohibition had been around since 1920, and over the course of the Roaring Twenties, Chicagoans had put up with beatings, robberies, and shootouts involving organized crime. It is still a tough town today, and back then, it might have been even tougher.

But when the papers came out telling of the massacre and showing the pictures, Chicago seemed as one to rise up and say, “Enough!”

The massacre was a brazen display of power, a message to anyone who dared challenge Capone’s control over the city’s lucrative bootlegging trade. It sparked public outrage and catapulted the notorious gangster into the national spotlight. The media, already captivated by Capone’s flamboyant persona, now painted him as a monster, a public enemy number one.

The Valentine’s Day Massacre wasn’t just a bloody chapter in Chicago’s history; it was the beginning of the end for Al Capone. His thirst for absolute control and his disregard for human life ironically became the very tools that brought him down. It served as a stark reminder that even the most powerful empires crumble when built on fear and brutality.

Only Capone Guys Kill Like That

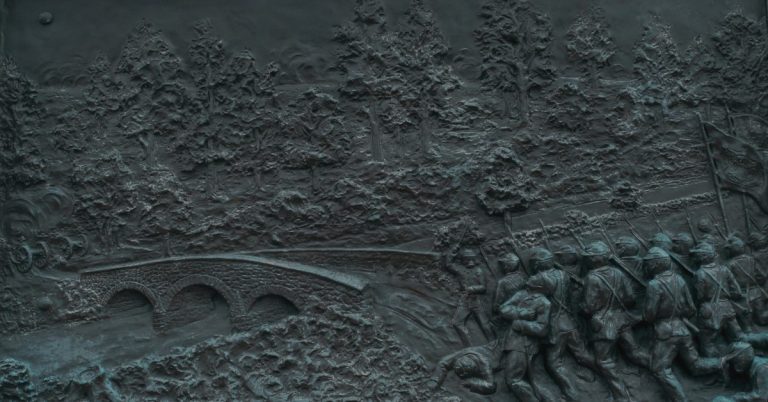

In a parking garage called Werner’s Storage, located at 2122 North Clark Street (across from a nice brownstone that today houses the Chicago Pizza and Oven Grinder Company), seven men were put against the wall and machine-gunned. Five of them were members of Moran’s gang, one was an associate of theirs, and the seventh man was some poor mechanic who should have taken the Day off. The coroner said there were 20 to 25 bullets in each of the victims’ bodies.

What confused everyone at first was how such heavily armed men allowed themselves to be disarmed, lined up, and shot. It made no sense. Eyewitnesses cleared that up. “Mrs. Alphonsine Morin, who lived across the street from the garage, was one of two witnesses who saw the assassins leave the garage after the massacre.

According to the Chicago Tribune, Morin saw two men who looked like policemen coming out of the garage after hearing the shooting. Both Morin and the other witness, Mrs. Jeanette Landesman, received a letter six days later advising them to ‘keep your mouth shut.'”

The Chicago Police Department had no record of any officers at the garage until they arrived to discover the dead bodies. Investigators deduced that two of the assassins had dressed as cops, while two or three others (the story varies) were dressed as civilians and entered the garage shortly before the gunfire. When the shooting was over, they left with the civilians, apparently under arrest. The civilians were also assassins.

“The landlady in the next building, Mrs. Jeanette Landesman, was bothered by the sound of the dog, and she sent one of her boarders, C.L. McAllister, to the garage to see what was going on. He came outside two minutes later, his face a pale white color. He ran frantically up the stairs to beg Mrs. Landesman to call the police. He cried that the garage was full of dead men.

The police arrived shortly after that and found the bodies. “Pete Gusenberg had died kneeling, slumped over a chair. James Clark had fallen on his face with half of his head blown away, and Heyer, Schwimmer, Weinshank, and May were thrown lifeless onto their backs.”

“Only one of the men survived the slaughter, and he lived for only a few hours. Frank Gusenberg had crawled from the blood-sprayed wall where he had fallen and dragged himself into the middle of the dirty floor. He was rushed to the Alexian Brothers Hospital, barely hanging on. Police sergeant Clarence Sweeney, who had grown up on the same street as Gusenberg, leaned down close to Frank and asked who had shot him. ‘No one — nobody shot me,’ he groaned, and he died later that night.” Even in death, he wouldn’t rat (mob slang for telling the authorities anything about a crime).

The Aftermath Of The Massacre

Although the entire city knew that Capone was behind the killings, there was nothing that the authorities could do. Capone was in Florida on Valentine’s Day, 1929. Bugs Moran had a public screaming fit when he found out what had happened, claiming, “Only Capone kills guys like that.”

Nobody was ever convicted of the murders. Two suspects, John Scalise and Joseph Guinta, were killed before they could stand trial. “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn was arrested but had an alibi. The killings destroyed the Northside gang’s ability to operate anymore, and they effectively made Chicago into Capone’s personal fiefdom.

However, Capone went too far with this hit. First off, the Chicago Police Department took a very dim view of its officers being impersonated in such an attack. While corruption in the CPD helped make Capone, the integrity of the department was not just tarnished but badly damaged by this.

The cops were no longer looking the other way. Second, the killings took place in broad daylight. The brazenness of the attack was a signal that the killers didn’t fear any retribution from a decent society. That always gets the papers and the politicians against you.

Third, and most telling, this wasn’t a fair fight. While there is a saying that there is no honor among thieves, there was a general attitude that guys getting shot in a firefight was a lot different than gangsters executing the opposition.

On returning to Chicago, Capone found things too hot for his liking. He and bodyguard Frankie Rio took off for Philadelphia. They were arrested on weapons charges and spent a year in the state penitentiary. After that, he returned to Chicago to run his empire, but in 1931, he was jailed for 11 years for the crime of not paying taxes on his illegally gained wealth. That is a useful thing to remember; it doesn’t matter how illegal a crook’s source of income is – the IRS wants its share.

The chilling memory of the massacre serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of unchecked power and the devastating human cost of criminal ambition. It stands as a sad monument to the lives lost on that fateful February morning, urging us to remember the sacrifices made in the fight against organized crime and the importance of upholding justice even in the face of profound darkness.

While the echoes of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre still resonate through the streets of Chicago, they do so as a cautionary tale, a chilling reminder of the fragility of peace and the dangers of unbridled power. It reminds us that even amidst the celebration of love and romance, the shadows of violence can lurk, a stark contrast that continues to challenge and haunt us to this day.