The battle of the Boyne was fought in Ireland in 1690 between two kings, James II and William of Orange, both of whome laid claim to the British throne.

On July 1, 1690, a significant event occurred in Irish, British, and European history. It was more than just a battle between two armies; it represented a clash of religions, monarchies, and ideologies that had far-reaching consequences beyond the battlefield. This pivotal moment had a significant impact on the course of history, and it is still remembered and studied today.

It was an unusual battle for a number of reasons, not least because it actually took place on July 1st, but because of the changeover from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar the day is now commemorated on the 12th of July.

The Background

Towards the 17th century, there were two claimants for the English throne – William and James. James was a Catholic, and William was a Dutch Protestant married to James’ sister. (William of Orange was actually married to James’s daughter, Mary. William was the son of James’s sister, also named Mary.)

William III claimed the throne of Great Britain in 1689. This also gave him a claim to the title of King of Ireland. However, James II still had control of many parts of Ireland. In July of that year James tried unsuccessfully to capture Derry. Later that year William sent 16,000 men to the North of Ireland, but they didn’t engage in any battles. In June of 1690, William came to Ireland to take command.

The battle for the supremacy of the English throne was also a battle to determine the status quo throughout Europe.

The southern Irish supported James, believing that he might be more lenient with Catholic Ireland than William. The Northern Irish, being largely Protestant, backed William.

This religious divide was seen throughout Europe, with English, Belgian, and French Catholics backing James and their Protestant fellow-countrymen backing William. William also had the support of a large Dutch contingent and some Swiss, Swedish, and Finnish mercenaries.

The Battle

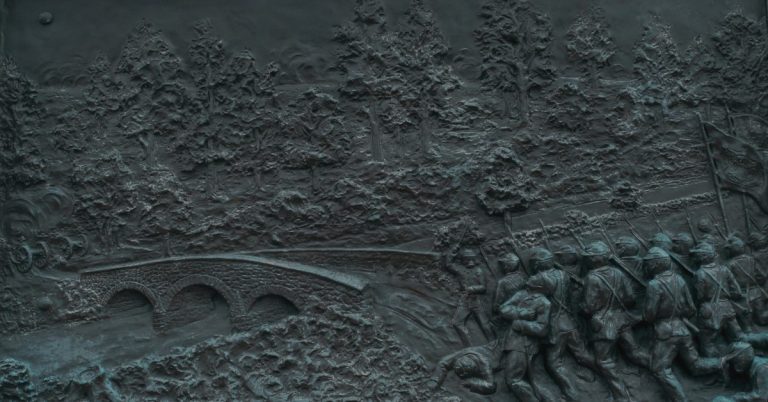

The two armies met at the Boyne River near Drogheda. James and his mainly Irish army of about 26,000 were on the south bank, and William and his followers, about 36,000 in all, were on the North.

The battle began in the early morning. General Schomberg led some 7,500 soldiers westwards, away from the battlefield, intending to attack further up the river and come upon James from the rear. However, this move was primarily a decoy, and James took the bait. He sent a large part of his army, including his most seasoned troops, to attack Schomberg’s men. Schomberg crossed the Boyne and marched North, tracked by the opposing soldiers. However, neither side attacked the other because there was marshy ground separating them.

In the meantime, William brought his main army from behind a hill and made a head-on attack across the Boyne using experienced Dutch soldiers. He also led his cavalry in person.

James himself did not lead his troops, withdrawing instead to a hilltop well away from the scene of the battle. It is widely believed that this difference in leadership styles played a large part in the swift victory of the Williamite forces. The Irish cavalry fought desperately to save the day, but they were outmaneuvered and were never able to recover the ground lost after being deployed by James against the decoy created by Schomberg.

Within a few hours, it was clear that the Williamites would win, and James retreated hastily towards Dublin. Several stories were told about his actions during the day.

One story tells of Sarsfield, an Irish General in the Jacobite army who was jeered by an opposing General following the defeat. He is reputed to have said: “Change Kings, and we’ll fight you again!” Another story tells of King James complaining as he reached Dublin that the Irish troops ran away. A woman who lost several relations in the battle apparently replied, “Congratulations, Your Majesty, on winning the race!”

The Aftermath

The immediate consequence of the Battle of the Boyne was the solidification of Protestant ascendency in Ireland, which would shape the island’s political and social landscape for centuries. The victory of William of Orange was celebrated by his supporters as a triumph for Protestantism over Catholicism, reinforcing a division that has had long-lasting repercussions. In the broader context, the battle was a key event in the “Glorious Revolution,” which ensured the continuation of Protestant monarchial rule in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and it played a part in shaping the balance of power in Europe.

In the years and centuries that followed, the Battle of the Boyne took on a symbolic significance beyond its military outcomes. In Ireland, it became a touchstone for the Protestant Unionist community, celebrated annually on July 12th. This date, known as “The Twelfth,” remains a focal point of celebration and, at times, contention, reflecting the deep historical divisions within Northern Ireland. However, recent years have seen efforts to reframe the battle’s legacy, focusing on its historical context and significance in the broader narrative of Irish and British history.

The Battle of the Boyne remains a fascinating study of how a single day’s conflict can influence the course of history, embedding itself into nations’ cultural and political fabric. Its legacy is a testament to the enduring impact of historical events on collective memory and identity, reminding us of the complexities of history and the importance of understanding the past in all its dimensions.

The Battle of the Boyne was a decisive European battle, one of the biggest battles of its time. The defeat of James left the throne of England, and with it control of Ireland, to William. The repercussions of this victory were felt right across Europe and persist in Ireland to the present day. On July 12th, every year in Northern Ireland, tens of thousands of “Orangemen”, so called because they commemorate William of Orange, march in celebration of the great victory at the battle of the Boyne.