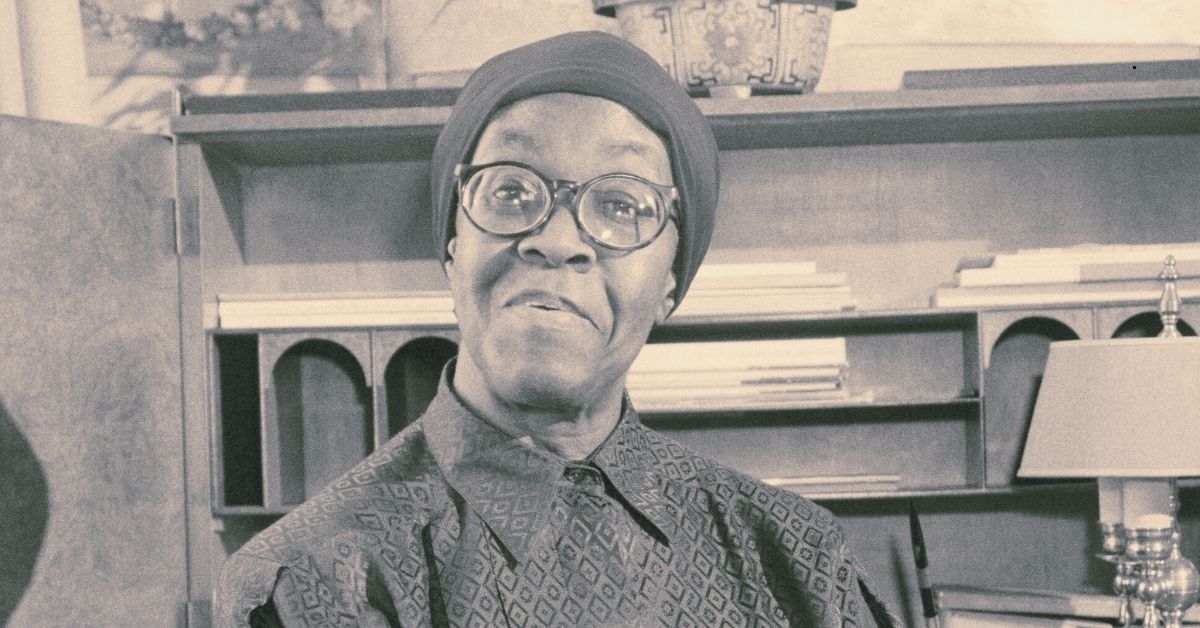

Gwendolyn Brooks’ life and work as a poet was marked by a persistent desire to be accepted and embraced by working and lower-class African Americans. Born in 1917 during the Harlem Renaissance, Gwendolyn Brooks was raised in a stable, two-parent household on the historically black, south side of Chicago.

Her mother, Keziah Corine Wims Brooks was a school teacher, and her father David Anderson Brooks, was a janitor. Having been told by her mother at the age of seven that she would be the “lady Paul Laurence Dunbar,” she dedicated her life to writing. Although her early poetry was about nature, the cycles of life, and other universal truths, over time her work became more distinctly black.

Her work reflected her desire to be appreciated and read by the masses of black people, as she pointed out in a 1974 interview with Haki Madhubuti, “Black poetry is written by Blacks, about Blacks, to Blacks. That is where I am now and expect to stay.” She was 57 years old.

| Full Name | Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks |

| Birth Date | June 7, 1917 |

| Birthplace | Topeka, Kansas, USA |

| Raised In | Bronzeville neighborhood, Chicago, Illinois |

| Death Date | December 3, 2000 |

| Place of Death | Chicago, Illinois |

| Occupation | Poet, Author, Teacher |

| Notable Genres | Poetry, African American literature |

| Most Famous Work | Annie Allen (1949) — Pulitzer Prize winner |

| Pulitzer Prize | 1950 — First African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for Literature |

| Other Works | A Street in Bronzeville, The Bean Eaters, Maud Martha, Riot |

| Education | Wilson Junior College (Chicago) |

| Spouse | Henry Lowington Blakely Jr. (m. 1939) |

| Children | Nora Brooks Blakely (daughter) |

| Positions Held | Poet Laureate of Illinois (1968–2000), U.S. Consultant in Poetry (1985–86) |

| Major Themes | Black identity, urban life, womanhood, civil rights |

| Legacy | Trailblazer in African American poetry, mentor to young writers, cultural icon |

Gwendolyn Brooks is praised for the role she played in mentoring and supporting many young black writers. At the age of 16 she reached out to Langston Hughes, who was a very prominent black writer at the time.

She was encouraged and given guidance by Hughes and other notable black writers, as she continued to write prolifically. This was a tradition that she experienced while developing as a poet, and dutifully paid it forward.

“Becoming very active in the poetry workshop movement-and perhaps more notably in poetry classes and contests for inner-city children, to which she devoted tremendous energy and gave both financial and personal sponsorship.” (Cary and Finkelman 184).

She graduated from Wilson Junior College in 1936, and published her first acclaimed book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville in 1945. At the suggestion of her publisher (Harper and Row) in 1944 to write what she knew, A Street in Bronzeville focused on her experiences and observations growing up in black Chicago. This shift in thinking was the beginning of a life-long commitment to writing Black poetry.

In 1949, she won a Pulitzer Prize for Annie Allen, her second collection of poetry. Brook wrote only one novel, Maud Martha (1953), which was partly based on her brief experience working as a maid after graduating from Wilson.

1967 marked a huge shift for Gwendolyn Brooks work, as she became immersed in the “black arts movement,” which was a product of the Civil Rights Movement.

“Brooks experienced a change in political consciousness and artistic direction after witnessing the combative spirit of several young black authors at the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University” (Gale 2).

Her black consciousness was sparked, and until her death, she dedicated herself and her work to the goal of black unity. Her most popular poem is generally agreed to be We Real Cool (1966), which addresses the social and political issues within the black community at the time, but communicates them in the black vernacular in a very attractive and catchy rhythm.

Although Gwendolyn Brooks’ life and career was undoubtedly impacted by being a woman, it did not define or inform her work as much as being black did. She married in 1938, just two years after graduating from college, to Henry Blakely, and she had two children, Henry Jr., and a daughter, Nora.

She consistently wrote for and about children, and was an advocate for their rights and needs.

Notable works for children include:

- Bronzeville Boys and Girls (1956)

- Aloneness (1971)

- Children Coming Home (1991)

She tried to remain neutral in the feminist movement, as she explained in an interview where she was asked how she felt about women’s liberation.

“I think that that’s another divisionary tactic that we need to be very wary of. We should be about Black liberation-which includes women and men” (Gayles 83).

Gwendolyn Brooks was described as a quiet, dignified, and shy person, a quality that stemmed from her childhood, where she was neither rough nor tough enough to fit in with the street kids of Chicago’s south side. Despite her incredible intelligence and talent, she was not “light-skinned” with “good hair,” and therefore unable to fully integrate with the black bourgeoisie.

This duality was a part of her, and was reflected in her efforts to fit in and be accepted by her own people.

“She is an intellectual poet who wishes to be otherwise in order to reach the masses of her people” (Gayles xvi).

Brooks wrote and published until her death at the age of 83, in 2000. Among a long list of impressive awards and honors, Brooks has been given over 50 honorary degrees, two Guggenheim fellowships, the title of Poet Laureate of Illinois (1968), named the Jefferson Lecturer by the National Endowment for the Humanities (1994 and 1995), made a poetry consultant to the Library of Congress, and given the National Medal of Arts award.