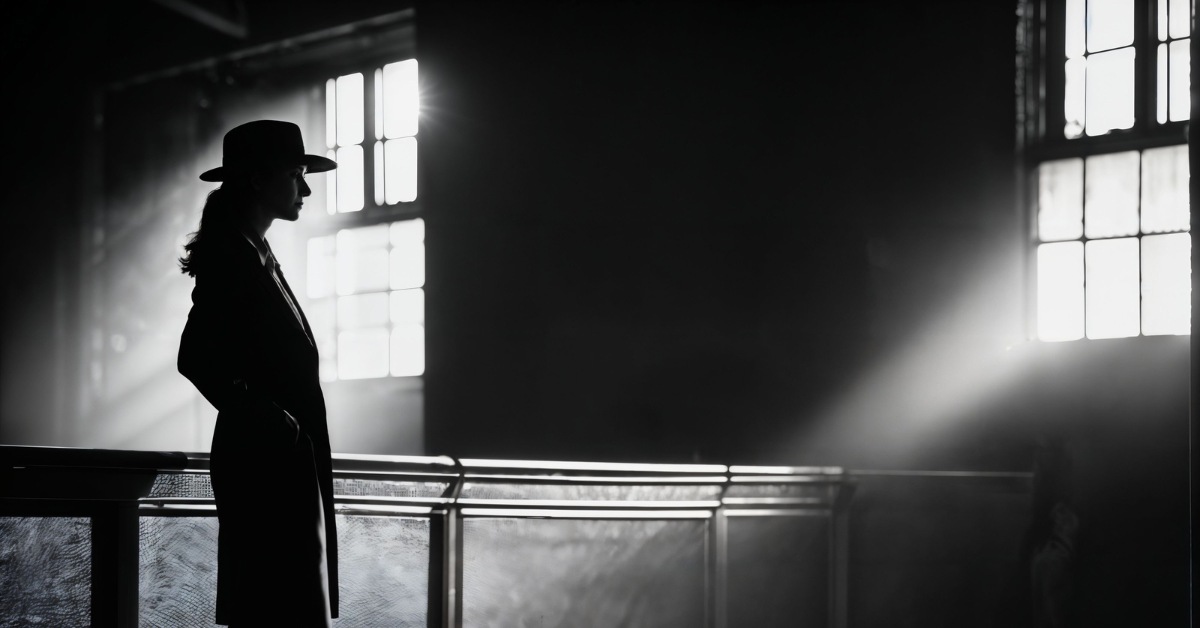

Film noir, a genre that flourished in the 1940s and 1950s, is renowned for its dark, stylistic aesthetics and morally ambiguous storytelling, reflecting the tumultuous period following World War II. This era witnessed significant shifts in societal structure, including the roles and perceptions of women, both in reality and as mirrored in the cinematic world. In this article, we delve into the elusive portrayals of women in film noir and explore the morale effects of the post-war period, uncovering how these cinematic narratives served not only as entertainment but also as a reflection of the complex interplay between gender, morality, and the societal aftermath of war.

The majority of the world’s countries were at war. Virtually all countries that participated in World War I were involved in World War II.

This global conflict incorporated new social realities in America. Headlines appeared: “16,000,000 Women; What Will Happen After?” asked the New York Times Magazine in 1943; “Watch Out for the Women,” cautioned a 1944 Saturday Evening Post. These headlines, among others, reflected the need for women to join the workforce during World War 2 to support the economy and help sustain the home front. On August 9, 1945, the atomic bomb was dropped on Japan, and on September 2 of the same year, Japan officially surrendered – World War 2 ended.

Soldiers returned home, and working women were supposed to quit their jobs to return to the life of homemakers/housewives. However, society has changed. The war had lasted for several years – jobs were scarce, and divorce rates rose. Moreover, women had learned to become the breadwinners and independent of men. This social change represented conflict because most men at this time portrayed women as homemakers. Social conflict is the struggle among individuals over something of value in society.

Marvin Olsen, a sociologist who studied post-war effects, stated that “all societies depend on change; change, in turn, depends on social conflict.”

Social conflict reflects and pertains to the aspect of power: dominate and subordinate. This aspect of social conflict was seen in post-war cinema, which portrayed attributes of power in various social and gender roles. Furthermore, social conflict is expressed in the rise of film noir and the conquest or doom of the femme fatale.

This rise in film noir represents the post-war society and depicts the portrayals of women. Nonetheless, the stereotypes and roles of women depicted in film noir were prevalent during the post-war years because of the insecurities and realities of an American society adapting to change. Moreover, these stereotypes and roles of women represent the changing society of the 40s.

Film Noir is a form of German Expressionism and became popular in America in the 1940s. Noir manipulates manner, mode, tone, and style and reflects the fantasies of a disdainful reality. Moreover, noir is distinguished by a serious, somber, gloomy tone; fast pace; complex texture; exaggerated realism; unusual angels and perspectives; voice-over narration; frequent flashbacks; settings mostly urban, interior, and nocturnal; and a moral postulate whereby corruption is not limited to bad individuals but pollute all of society.

Likewise, this manipulation within film noir reflects and depicts the gender roles and stereotypes of women. Film noir, directly and indirectly, imitates the social roles and stereotypes of women in film with the social reality of women’s lives.

The roles and stereotypes of the post-war period were relevant because of the war crisis. The role of the good woman and the stereotype of the femme fatale represented the values and attitudes of society. These values and attitudes also represented the (political and social) insecurities of the time.

The crisis of the war affected women and changed the roles and stereotypes of women in society. The iconography of film noir represents women in conventional and contemporary ways and illustrates the reality and fantasy within society.

Types of Women in Film Noir

There are three basic types of women in film noir – a femme fatale, the good woman, and the marrying type.

A femme fatale is an unjust woman who uses her sexuality to capture the unfortunate hero. This “deadly woman” is typically portrayed as a sexually charged, strong, independent, and magnetic woman. These traits include greed, selfishness, and insensitivity. On the contrary, the good woman embraces her traditional “role” in the family as a homemaker, is passive and monotonous, and is dependent on men.

The good woman is nurturing, non-threatening, and submissive to conventional values. Lastly, the marrying type is a combination of the femme fatale and the good woman. She could be just as threatening as the femme fatale or just as dull as the good woman. Furthermore, all three characteristics of women in film during the post-war years rely on cultural types and or stereotypes. The femme fatale represents a direct attack on traditional values, which the good woman cherishes and conforms to. The femme fatale refuses in this sense to play the “role” of devoted wife and loving mother that society set for women. Furthermore, she finds marriage to be confining and loveless. Unlike the femme fatale, the good woman lives and represents family life and the notion of homemaker.

The marry type ironically represents the ideal perfect wife of a girlfriend. I suppose this is culturally significant because the marrying type seems to accept without question the rules that society prescribes for marriage and family.

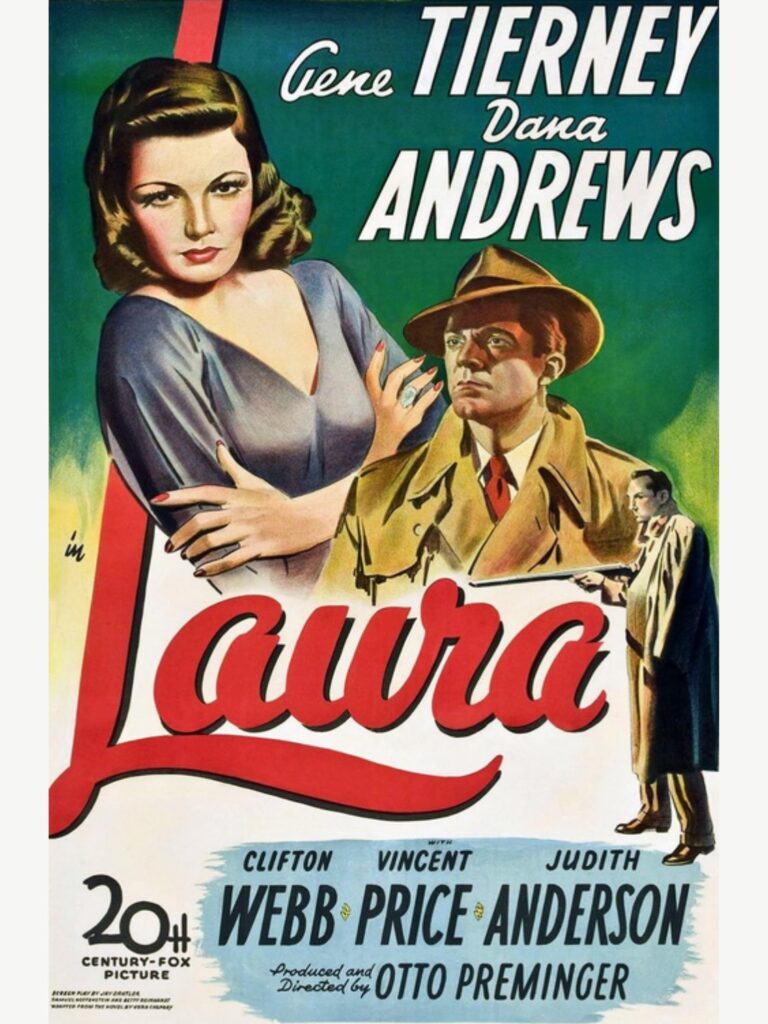

Laura (1944) marked the era for post-war film noir. The initial flashback in Laura includes a voice narration that describes Laura’s charm and personality and “unformatted death future perfect tense.” This charm and mystery compel the detective to daydream and fantasize about the life of the elusive Laura. His fantasy becomes a reality when he discovers that the “dead’ Laura is alive. Laura is caring and likable and easily represents the marrying type of woman in noir.

In Double Indemnity (1944) and Murder, My Sweet(1944), the femme fatale prevails. These two films were released two months apart and share similarities. In both films, the femme fatale is a beautiful, bleached blonde who makes an effort to hide her fatal intentions. Likewise, in both films, the femme Fatima has a stepdaughter who competes for the male protagonist.

In Double Indemnity, Phyllis is the ultimate manipulator when she persuades Walter to kill her husband. When Walter is caught, he explains his motives: “I killed him for money- and a woman. I didn’t get the money, and I didn’t get the woman.” This is a double indemnity in itself because Phyllis never wanted him and only used him to kill her husband. Phyllis’s character is dominant, strong, and assertive. However, these characteristics do not represent post-war values. Therefore, Phyllis is a deviant and must be murdered.

At the end of the movie, Walter takes the gun out of Phyllis’s hand and eventually kills her. The notion of Walter taking the gun out of Phyllis’s hand represents women’s powerlessness and subordination to men during the war.

Jon Tuska, the author of Dark Cinema: American Film Noir in Cultural Perspective, states that femme fatales in film noir are usually subsequent to the male protagonist.

However, the male protagonist in the film is usually alienated from his environment, and one of the principal factors behind this alienation is the fact that the femme fatale is in possession of her own sexuality. This independence leads to severe punishment during or by the end of the film, whereas the femme fatale is punished for this independence, usually by death. Nevertheless, the consequence represents the balance of power between women and men. As Tuska suggests, if the woman is more independent, then this independence must be destroyed by the male in order to gain his identity of masculinity in society.

An aspect of this is also depicted in Mildred Pierce (1945). Mildred Pierce is different from other film noirs during the post-war years, though, because the main protagonist in the film is a female and is brought down by another female – her own daughter, the femme fatale.

Mildred Pierce is significant in film noir because it portrays the relevant society of the time. In 1945, women participated in a double life: they were housewives and workers. At this time, the economy was scarce because of the war, and women needed to join and, in some cases, stay in the workforce. Also, at this time, divorce rates were rising, and women needed to become the dominant breadwinners in some cases. This relates to Mildred Pierce because, at the beginning of the film, we realize that Mildred cannot rely on her husband to provide for the film – he is unemployed.

The ironic thing here is that he is unemployed and having an affair. This affair leads to divorce, and Mildred is forced to enter the workforce to provide for her family. She finds her career in the kitchen and begins to establish successful chains of restaurants. As Veda (daughter) gets older, Mildred’s success degrades her. Veda is status quo, and the idea of working in a kitchen demeans her persona. Veda becomes the femme fatale who contradicts and clashes with the good woman (Mildred). Symbolically, the film tells us that it is Mildred’s fault for the way her daughter is. Perhaps this representation is depicted by Mildred’s success as a businesswoman and mother. However, during the post-war era, it was impossible to even conceive of a woman as a successful businesswoman and a mother.

Moreover, the film shows that if a woman prevails and tries to triumph to the top, then her kids will be doomed by corruption. This indirectly relates to the author Tuska’s opinion about independence and women in film noir. Meanwhile, Mildred became successfully independent in a man’s world and, in turn, corrupted her daughter. Furthermore, the last scene in Mildred Pierce implies Mildred and her ex-husband’s reunion.

This reunion symbolically leaves Mildred as the subordinate and her ex-husband as the dominant redeemer.

A year after Mildred Pierce’s film noir soared. 1946 marked the peak of film noir. On the technical side, the technical hardware of the American studios was the best in the world. The studios had the resources and the locations to make exquisite films. Some of these technological changes in film noir included urban locations, night shooting, and chase scenes.

These industrial changes were important and relative to the social condition of the post-war years. Unemployment and the rise in crime became essential topics in 1946 film noir. Moreover, these social and existential issues provided opportunities for more realism. This realism portrayed the moral, political, and social values of the day.

Films of 1946 included The Killers, The Big Sleep, Gilda, and The Postman Always Rings Twice.

The Killers: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0038669/ The Big Sleep: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0038355/ Gilda: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0038559/ The Postman Always Ring Twice: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0038854/

A social and cultural example of this is shown in The Killers through a few images that represent boxing. Boxing had become one of America’s favorite sports. The Killers portrayed a few images of boxing to intrigue the audience.

Gilda (1946) represented eroticism and depicted an “evil woman” femme fatale who is not really evil but who is forced into a behavior that looks evil because men want her sexually. This social construct represents the desires of men and the stereotypes of society that her body and looks reflect who she is. This gives women a double standard and perceived misconception. Gilda’s portrayal of a sexual woman reinvented the femme female’s morale. Furthermore, it reinvented the notion of the female fatale being punished in society. Gilda was penalized for her sexuality; however, she fought back by using her “assets” to perform a striptease at the casino. This representation, whether negative or positive, leaves women with a feeling of worth. Gilda represents the possibility that women can succeed in a male-dominated society. The femme fatale, in this case, overthrows destruction and earns her freedom.

The social conflict expressed and portrayed in the femme fatale is the exact opposite of the traditional concept of a woman. She deviates from the conventional role of women as housewives and mothers and explores herself in new roles. This social conflict arising from the conception of the fatal woman (femme fatale) is just one representation of the dramatic change in women’s roles in American society and during the war years.